Jo Hess was always too busy sculpting to keep track of news articles written about her. Only a few were found in her files. Her art speaks for itself.

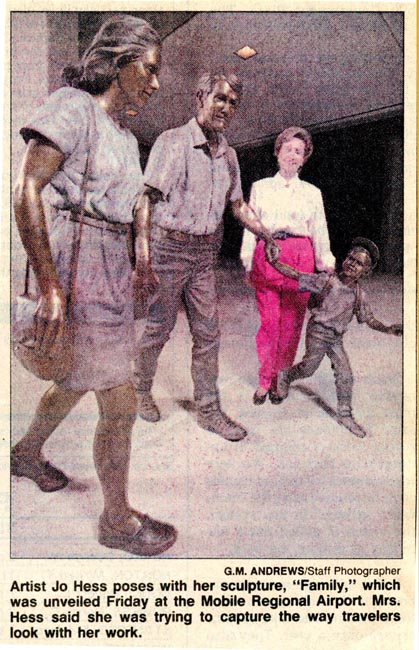

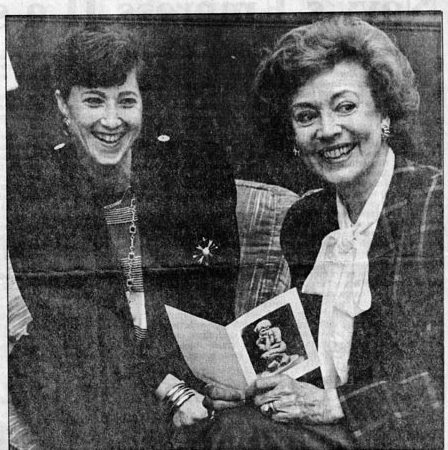

Below is the text of an article that appeared in the Mobile Press Register. Unfortunately the publication date has been cut off our copy of the article, but it was in the fall of 1994. The photo shown here appeared along with the article in the Press Register.

“Family” is the newest sculpture to grace the grounds of the Mobile Regional Airport.

“Family” is the newest sculpture to grace the grounds of the Mobile Regional Airport.

Created by Mobile artist Jo Hess, the life-size bronze piece was unveiled at a reception at the airport’s M.C. Farmer Terminal Friday evening. The sculpture is the third piece for the airport, according to Murray Cape, chairman of the Mobile Airport Sculpture Fund. Cape spearheaded the fund-raising campaign for the $100,000 sculpture.

He said money for the commissioning of the piece, handled through the Mobile Arts Council, was raised through the sale of $500 parking spaces at the airport and donations from individuals and several local companies.

Mrs. Hess said her sculpture is the culmination of 2% years of work and 300,000 flying3. miles between her home in Mobile and her studio in Loveland, Colo.

“I had ample opportunity to observe my fellow travelers,” said the artist, whose bronze works are scattered throughout the city and whose life-size garden sculpture has a permanent place at the Fine Arts Museum of the South.

The Mobile native says the life-size bronze sculpture is the largest work she’s ever done. “l have a 15-foot ceiling in my studio and l didn’t have enough space to spread out,” she said. Rather than give up, Mrs. Hess completed the busts at her Colorado studio, then did the body work at a friend’s studio. She used professional models and video images she took during her own travels to get the faces and movements just right. “l wanted to do something for the city,” she said. “Anytime you have a lot of art in a city, it means the people love the city and want to make it beautiful. l wanted to be a part of that.”

Mrs. Hess said her original idea for an airport sculpture included a business man with a briefcase, returning from a trip and being welcomed with outstretched arms by his family. “But I think this piece captures the way people really look when they’re traveling,” she said. “l‘m very pleased with it.” The family in Mrs. Hess’ sculpture is dressed casually — blue jeans and T-shirts, with the little boy wearing a baseball cap.

Mobile Press Register

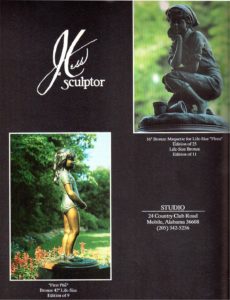

In the late 1990’s the publication “Artists of Alabama” featured her work in Volume 1 of the series.

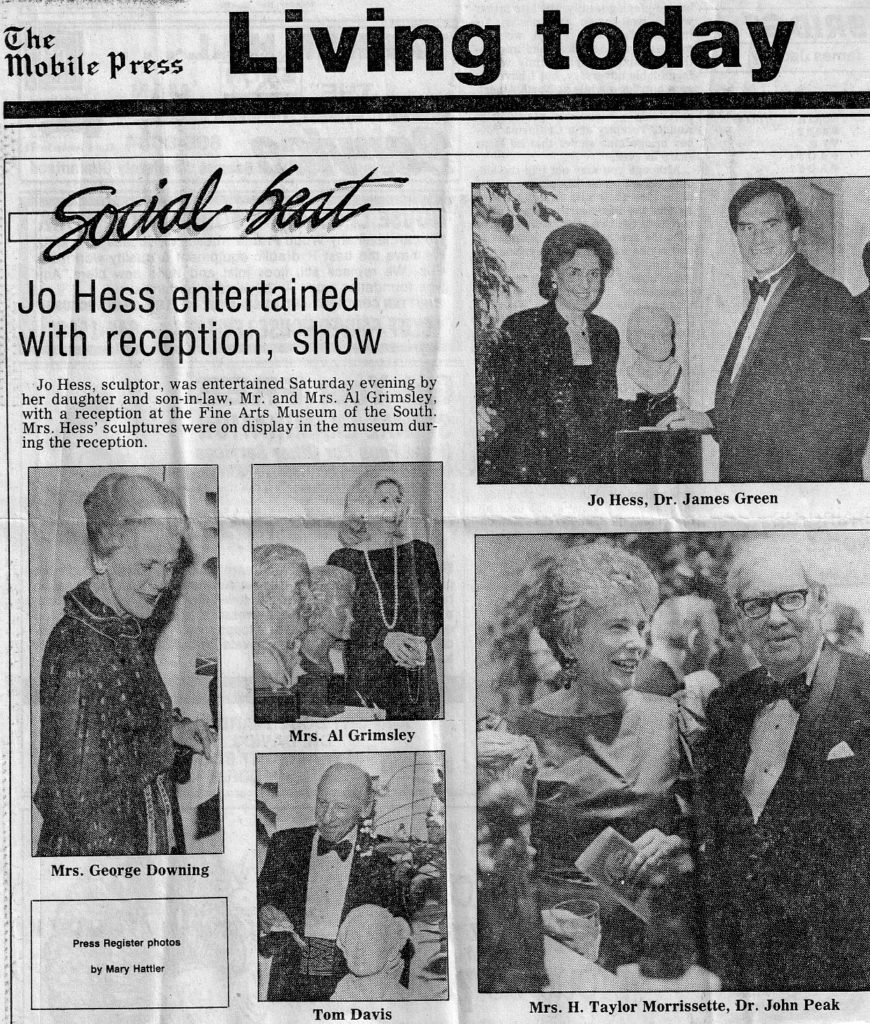

Sculpture by Jo Hess installed on patio at FAMOS

Article in Mobile Press Register October 15, 1989, by Gordon Tatum Jr., Fine Arts Editor

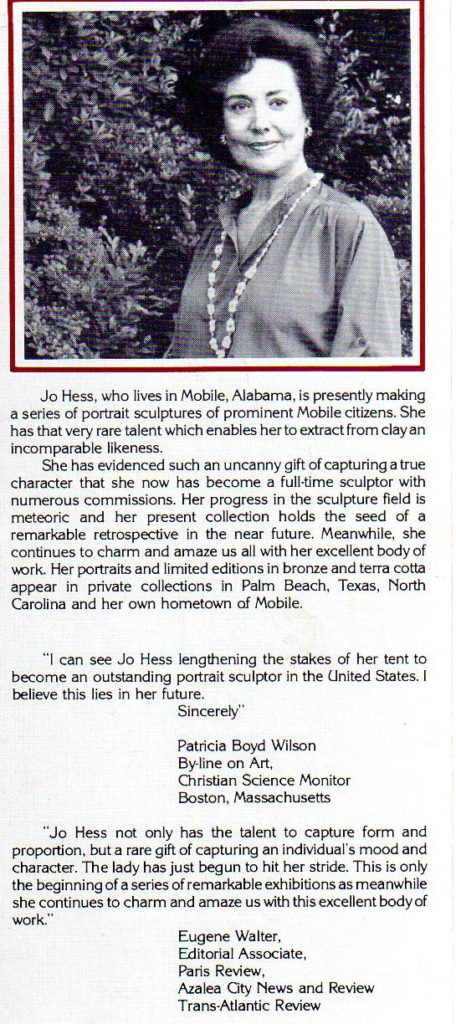

Her hands are almost frail, and soft, with slender fingers, sensitive. Jo Hess could have been a pianist. She is a sculptor and her reputation is considerable. “Flora,” one of her pieces, has been installed at the Fine Arts Museum of the South.

It can be found on the patio. “Flora” is a purchase of the Art Patrons League.

“I have always painted,” she said. “I studied with Carlton Furbush and Geneive Southerland. Sculpture did not appeal to me. But I bought a bust of a man in an antique store. And I bought some clay, eventually. He just stood looking back at me,” Mrs. Hess said.

She studied with Bruno Luchessi, a well-known Italian sculptor who also has a studio in New York City. “He had written the textbooks we were studying. Then I started going to Scottsdale School every January. A group of artists-friends and I convinced Luchessi to teach us. I’ve had the best training,” the Mobile artist said.

Mobile Press Register photo by Roy C. McAuley, chief photographer

Mobile sculptor Jo Hess holds note paper, a project of the Art Patrons League, which depicts her bronze sculpture “Flora”, now a part of the permanent outdoor collection at the Fine Arts Museum of the South in Langan Park. She talks with APL JoAnne Fusco, chairman of the public arts and crafts acquisition committee, which purchased the work for the FAMOS patio.

“We had to add a room on our house in Mobile. I now have a studio in Loveland, Colorado. I love to do animals, people, even well-known personalities. But I started with busts, then l grew to figurative sculp- tures. The original “Flora” was only 16 inches high. I call her my garden girl,” the sculptor said with sparkling eyes.

Her clay comes from Pennsylvania, but lately Mrs. Hess has found clay as close as Pensacola. “There is a water base, an oil base and now a combination — petroleum, water base and beeswax. That holds the moulds better. Tiny lines hold up better. One of the artists in the community (Loveland) develops it. He does big works, such as bears and elks.”

“l entered a show there recently. We were allowed four pieces in the show. Collectors came from as far away as New York City. Loveland is a small town near Denver. The large sculpture show really brings in the crowd,” she said. JoAnne Fusco, chairman of the public art and crafts acquisition committee of the Art Patrons League, said people liked the faces Mrs. Hess creates. “Her work has a certain glow, if that is possible. It has a sweetness,” she said.

Mrs. Hess says she puts a lot of images together. She has her own darkroom. She shoots the subject, taking from 24-48 pictures in the round. Then enlarges them. “l have 120 black and white on one man,” she said. Then she starts the armature of wire which she covers with aluminum foil.

She then cuts pieces from the square of clay and applies them, starting with the thrust of the neck. That, she said, takes fairly quickly, as quickly as one day. “l do a lot of detail work. l’ve even had one plastic surgeon ask to come out and learn from me,” she said.

It takes about three sittings. “You have to have patience, and l love working with children. Her creation is then boxed by her husband, Charles, who builds the crates. “He is wonderful and my support.“

This wire cage is attached to the base of the armature. “l meet the mould maker at the airport (in Denver). He makes the mould after l’m done. He applies the rubber mould and lets it dry, then the mother mould or plaster surrounding it,” she related.

Her foundry is also located in Loveland. They pour the wax. That is when she flies back out. “The seam lines have to be done away with. Next comes the sprewing department where they attach the long sticks of wax, the pouring holes (as well as air vents) where the bronze goes in.

According to Mrs. Hess, after the sprewing room comes the ceramic shell form. This is sand in a slurry. About 15-20 coats are applied. it is dipped and allowed to drip and dry. The wax is all over. Then the work goes into the oven. As the wax melts it runs out to the side and is disposed of. That is where the lost wax method comes from,” she said.

Huge crucibles are used for pouring molten bronze into the sprews or pouring holes. What follows is the welding room. There the sprews are cut off with torches, then the piece is welded back together. Next comes the metal chasing where details must go back on if any have been lost. After that it is time for sand blasting all impurities. (See a video of this process here.)

Patina comes after that. “We use acids depending on what colors you want, then the sculpture is mounted on a marble base. lt’s somewhat like a newborn. But it only took three-four months for the average bust. lt’s usually two months before I‘m satisfied with my work. ‘Flora’ took longer. When there are hands it is more difficult,” she said.

Mrs. Hess used Mobilians Gary LeFevre and Bradley Smith as models for “Flora.”

She admits that her work as a sculptor was not so well known until she received two commissions from families in France. Part of the agreement was that she would personally deliver the works of art and see to their installation. From that time on her career as a sculptress has grown.

“I started in oils and pastels. My first “sculpture was a little abstract piece. I prefer to work in clay in the realism style. But it looks as if that will grow into something else,” she said.

Mrs. Fusco, who is assisted by Angela Crowell as co-chairman of acquisitions, said funds from the Outdoor Arts and Crafts Fair were used to purchase “Flora.” She said more contemporary art in an outdoor setting may be forthcoming.

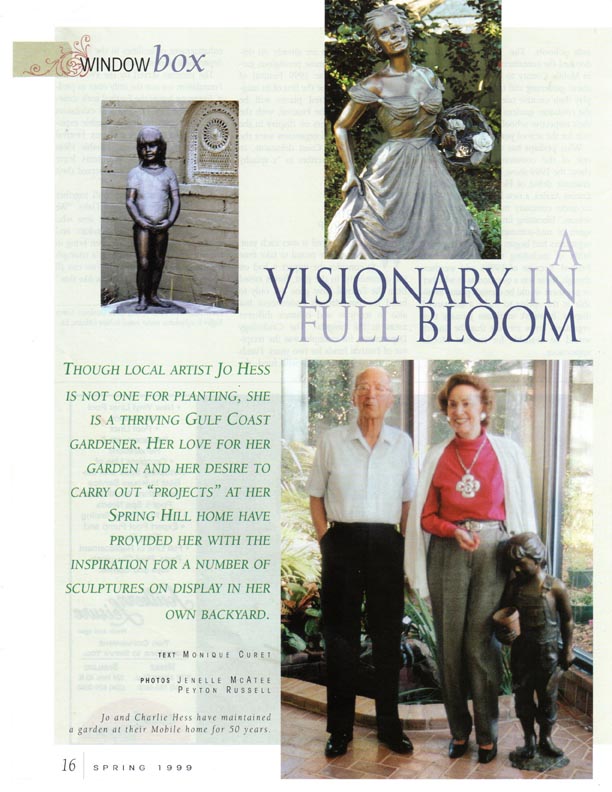

A Visionary in Full Bloom

This article by Monique Curet appeared in the Spring 1999 issue of Gulf Coast Gardener

Mobile sculptor Jo Hess is not an avid gardener, but she has reaped inspiration from her garden time and again. Her ability as a sculptor earned her commissions for pieces on display throughout Mobile and the United States, and those pieces of art, she is proud to say, often had humble origins in her own backyard garden.

Mobile sculptor Jo Hess is not an avid gardener, but she has reaped inspiration from her garden time and again. Her ability as a sculptor earned her commissions for pieces on display throughout Mobile and the United States, and those pieces of art, she is proud to say, often had humble origins in her own backyard garden.

Jo and Charlie Hess have faithfully maintained a garden at their home in Country Club Estates throughout their fifty years of residence. In their younger years, the couple would pool ideas for their garden and “work it out together.” While they collaborated on the yard’s scheme, Charlie was the gardener among the two, responsible for taking their plans to completion. “I only garden in small quantities, as the mood hits me…and that’s in small quantities,” Jo Hess says. Charlie’s inclination for planting comes naturally His mother was “quite a gardener”- twenty-five-year-old amaryllis, her gift to the couple, still bloom in the Hess garden each spring as testimony to her talents.

While Charlie and his mother enjoyed planting, ]o harbored more enthusiasm for undertaking projects in her garden. Her early projects pre-date her years as a sculptor, such as the time her 13-year-old son helped her to dig the small fish pond occupying a corner of a now glassed- in patio. Later, as a practicing sculptor, Hess used her artistic vision to enliven her garden, and she used her garden to enliven her artistic vision.

“I usually get ideas in summertime, when I am swimming and floating,” she says. “I think, ‘I’d like a sculpture here, or a garden there.” Her ideas primarily emerge in this manner, as she envisions what she would like in a certain spot. She is also quick to credit her “gift,” the impetus of her ideas for sculpture. “It just comes,” Hess says.

This gift of vision did not manifest itself early in her life. A self-described “Grandma Moses,” she did not begin sculpting until in her late 40s when a sculptor friend motivated Hess to explore her interest in that art form. After discovering her latent talent, Hess devoted four years to mastering the art. She studied at the Scottsdale Artist School in Arizona, the University of South Alabama and Spring Hill College; practiced under famous sculptors; enrolled in anatomy courses; and read “scads” of books. Finally, an Italian sculptor told her that she had learned enough and that all she needed to do was sculpt. The advice was all the encouragement she needed.

In 1983, Hess began spending her weekdays in Colorado, and there she fashioned life-size sculptures from bronze. Her studio’s location was based on convenience; a foundry was nearby, and the moldmaker maintained a studio beneath hers. She quickly gained recognition for her work, and a practice that began for pleasure developed into a business. She was commissioned to sculpt approximately 40 pieces, including works on display in the Mobile Chamber of Commerce, Providence Hospital, Cooper Park, University of South Alabama, Mobile Museum of Art and Mobile Regional Airport.

Hess delights in the knowledge that she was able to make a cultural contribution to the community. “I am glad because l can leave something to Mobile and in other cities which will be here long after I’m gone,” she says.

Hess delights in the knowledge that she was able to make a cultural contribution to the community. “I am glad because l can leave something to Mobile and in other cities which will be here long after I’m gone,” she says.

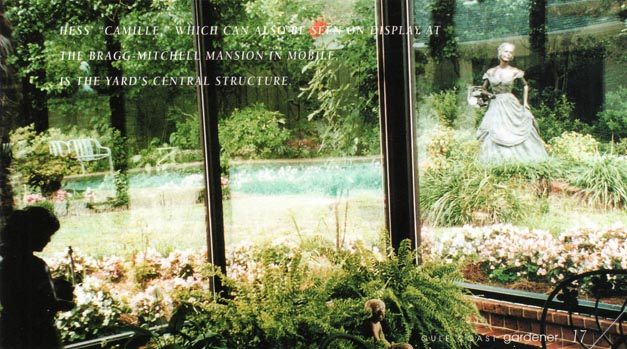

Her pieces for public display are numerous, and her garden also abounds with examples of her work, pieces inspired by her vision for her garden. Hess says she knew during the planning stages of “Camille,” the yard’s central sculpture, that she wanted the piece to include a basket of flowers. The work features a young girl in a period dress, her right arm sweeping the air, a basket of camellias over her left.

The process involved in creating the camellias’ likeness is an indicator of the careful deliberation and work involved in sculpting each piece. The flowers were modeled after camellias taken from a friend’s garden. To master the precision of each camellia bloom upon returning to her Loveland studio, she carried the blooms on the plane to Colorado, then stored them in the refrigerator to be used as she needed them. A replica of “Camille” is found in the camellia garden at the Bragg- Mitchell mansion.

Another sculpture found in the Hess garden is appropriately named “Flora,” for the goddess of the garden. Its subject is a fitting tribute to an art which has played a key role in Hess’ development and work as a sculptor.

Hess ranks her garden, along with music and good health, among the three things most important to her. However, health is what prevents her from continuing to sculpt life-size bronzes; the chemicals used in the process proved damaging to her lungs, and so she ceased using the metal. Having closed her Colorado studio in 1998, she now plans to resume painting, which she practiced before sculpting; to sculpt in clay; and to continue one of her favorite works in progress: her garden.

Though Hess and her husband no longer tend their garden themselves, they continue to corroborate on its contents. She still has visions of what she would like in her yard. “My husband says when I get real quiet, he knows some idea is coming up.”

Through her lengthy and successful career as a sculptor, her garden has served as the source of her inspiration. The reason for her motivation she says, is simple: “If l can see beauty around, I am inspired.”

Author Monique Curet is a freelance writer attending Spring Hill College.